How to adjust your guitar

intonation

In this article you will find instructions and tips about the intonation setting of electric guitars (on acoustic guitars it is factory compensated). This is part of the general setup of the guitar, that involves topics covered on the Soundsation blog, as neck truss-rod and action adjustments.

Before continuing with intonation

setup you should have:

- your usual strings

well installed and tuned

- a reasonable neck relief

- an action adjusted according to your taste

All that verified, we can talk

about self-adjusting the intonation by acting on bridge saddles.

Foreword

Many people could ask why it is necessary to adjust

their guitar intonation. Isn't it already in tune when the strings have been

tuned? Actually, guitar (as bass) is not a perfect instrument from this point

of view, and will never be. In fact, it reveals an intonation mistake

due to fret positions, fixed and equal for all strings though they have

different gauge, tension and manufacture. This mistake is spread through

the fretboard so as to optimize a correct intonation feeling, approximating the

so called equal temperament, without being perfectly in tune in all

positions.

We are just tuning plucked

open strings; afterwards it is necessary to compensate the differing

lengths of six or more strings when we press them on different frets. In this

matter are involved: fret installation and finishing, action, quality of strings, gauge, pull and build, all topics you can find on our blog.

A hint about scales

Let's say some words about an

instrument scale (not the neck or fretboard scale, as

someone often says): it is the distance from the nut (or zero-fret) to the 12th

fret multiplied by 2. In theory this calculation should give us the precise

length of the string from the nut to the bridge saddle centre.

Actually this is not true. In fact, given the variable position of the bridge

and its saddles, each tuned string has its own length on that

instrument, the one that allows a production of notes as accurate as possible

on any fret. You can take as a reference the B or second string, ensuring that

the scale is nominally exact for it and gradually adapted to the other strings.

For example this is useful to find the right position of a jazz guitar moveable

bridge.

The most popular scales

are:

- 628 mm (24-3/4”), typical of almost every solid-body and semi-hollow Gibson – though it has been subtly varied over the decades – and guitars inspired by them

- 647 mm (25-1/2”), used for almost all Fender electrics and the guitars inspired by them, also a few Gibson jazz guitars and a lot of acoustics

- 660 mm (about 26”), traditional for classical guitars.

Let's cite some more examples

among diverse scales:

- 635 mm (25”), used on

PRS electrics, Danelectros, Dobro and National resonator guitars

- about 625 mm

(24-19/32”), originally the Gretsch Country Gentleman scale

- 596,9 mm (23-1/2”),

very short, it is the scale of the Gibson Byrdland

- 609 mm (24”), another

short scale found on the Fender Jaguar

- 673,2 mm (26-1/2”), the scale of the major part of 7-string guitars

Obviously the number of frets has

nothing to do with an instrument scale, but the longer the scale, the more the

same number of frets are spaced.

In recent years, manufacturers use to indicate the scale length with mixed inch and decimal values, thus adding further confusion between millimetre and inch sizes. For example, the above mentioned Gretsch Country Gentleman scale is now officially specified with 24.6”.

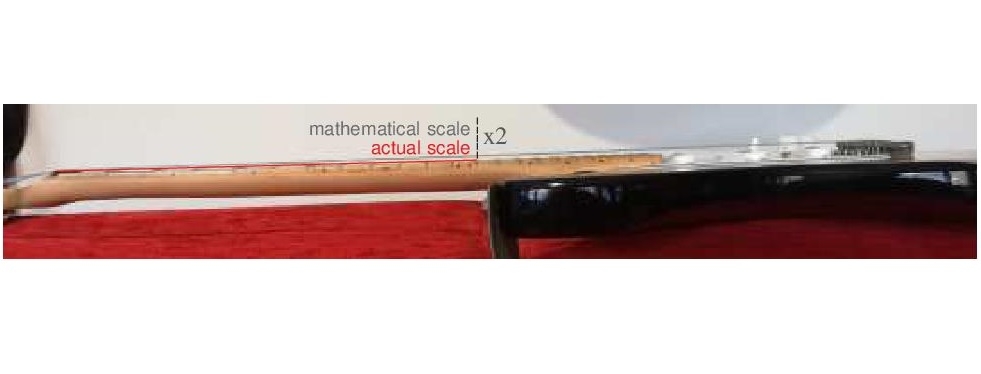

A little geometry

Let's imagine a scalene

right-angle triangle, the hypotenuse of which is represented by a string

stretched from nut to bridge (instrument mathematical scale), the

shorter cathetus by the bridge height and the longer one by the string pressed

on the fretboard (instrument actual scale). It's clear that the

hypotenuse and the longer cathetus don't have the very same length, with all

the consequences on the string segments determined by any single fret, for

instance when you are playing open and fretted note mixed chords. When you are

adjusting a guitar intonation all you are doing is trying to compensate for

the gap between mathematical scale and actual scale, that is between the

hypotenuse-string and the cathetus-string. I like to use the definition of

authors Franz Jahnel and Dan Erlewine (*) calling them respectively true

scale and singing scale.

Fixed bridge guitars

Intonation compensation it is not necessary on electric instruments that are equipped with a fixed wrap-around bridge without individual saddles, though it sometimes can show a set compensation. Modern versions often feature two Allen screws for horizontal shift.

In the same way, intonation

setting it is not necessary on most acoustic instruments, both folk and classical having a bone or plastic fixed saddle. They are almost

always very well built instruments, intonation is ensured by a perfect

bridge/saddle placement and possible fixed compensations for one or more

strings, usually the B (second) string.

Anyway, it should be specified

that fixed bridge and saddle drop or raising – both on electric and

acoustic guitars – can slightly affect factory set intonation. Replacement

of strings with others of different gauge and tension can also cause

intonation differences.

In any case intonation adjusting

of an acoustic guitar is possible, but it has to be entrusted to the

craftsmanship of a luthier.

You can turn to a luthier for

fixed bridge electrics too or think about replacing the bridge with an individually adjustable saddle replacement.

Let's go ahead!

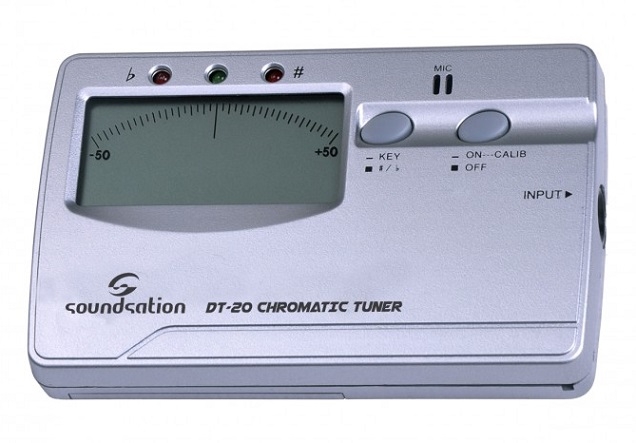

It's time to go ahead with

your guitar intonation. Once the guitar has been tuned, check by means of

an electronic chromatic tuner if the notes you get pressing the strings on the 12th fret are

equivalent to the octaves of the open strings.

For example, if you are tuning

the B string, you should get an octave up B at the 12th fret, well tuned,

neither sharp nor flat.

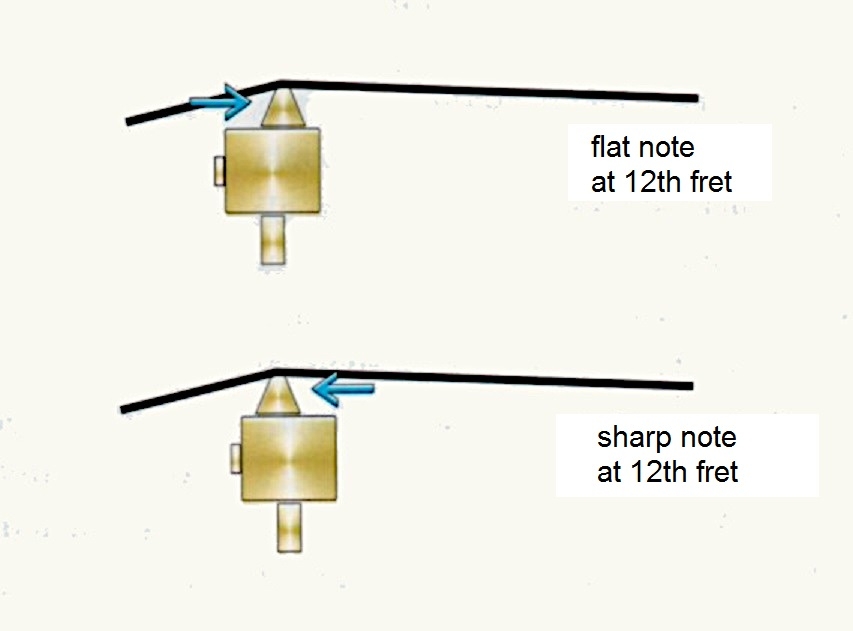

In case of a 12th

fretted flat or sharp note, you have to act with a screwdriver (sometimes

with an Allen wrench) on the screw that makes the B string saddle move:

- if the 12th

fret note is flat compared to the open string note, then make the saddle

move forward (towards the neck); in practice you are reducing the string

length: shorter string, higher pitch sound

- if the 12th

fret note is sharp compared to the open string note, then make the

saddle move back (towards the tailpiece), so increasing the string

length, as long as you get a correspondence for each string: longer string,

lower sound.

When you shorten and lengthen the

string, general tuning will change, so you'll have to patiently retune any time

you evaluate the octaves.

This applies both to tune-o-matic style bridges and vibrato (or vibrato (or tremolo) bridges) bridges.

Do not be tempted to make this

operation with the guitar laying horizontally on a work bench. You must compensate keeping the guitar as if you were

playing. Gravity has been performing its force for 13,8 billion years, on

guitar strings too.

Special cases

- Fender Telecasters

with vintage style bridges and guitars of other brands inspired by that design have one saddle for one pair of strings (please

read the setup of your guitar – PT 3the setup of your guitar – PT 3 on the Soundsation blog): perhaps you'll have to find a compromise

position. Luthiers and skilled DIYs succeed in modifying cylinder saddles as

needed. Fortunately, there are stunning Telecaster bridges with six individual saddles or three pre-shaped saddles for this purpose.

- Sometimes, on single

coil pickup guitars (especially Stratocasters), you could not be able to

compensate the intonation of wound strings, particularly the E (6th)

string. Nearly always the problem is a bridge pickup that is too close to

the string. Especially if the pickup has oversized or enhanced magnets, it

can act as a lace around the string, avoiding its free vibration. Just

raise a little the string or lower the pickup to get rid of the problem

- Most times classical guitars don't even have a factory pre-set saddle. This advantage is due to their long scale and to nylon strings that have more uniform gauges, tensions and individual action.

A few tips

In order to taste the effect of

your work, play some chords with fretted notes and open strings around the 12th

fret: if the guitar resonance is good, the more the chord is full, pleasing, euphonic,

the more the intonation is accurate.

Keep in mind that intonation

is steadier and easier to compensate on guitars with:

- a long scale

- heavy strings with a

considerable pull

- low action

On the other hand intonation

is more difficult to compensate on guitars with:

- a short scale

- very light and low

pull strings

- heavy wound strings

- high and/or very

diversified action from string to string

It's easy to understand the

reason why '50s, '40s and previous decades guitar manufacturers paid

little attention to intonation adjustment possibilities: today's popular light string sets, such as .010-.046 and .009-.042, were yet to come.

Intonation improvement efforts

I'd like to mention few

interesting solutions – though partially successful: the Buzz Feiten Tuning

System and the Earvana Compensated Tuning System, that fundamentally

are nut modifications aimed at improving the instrument general intonation, but

have to be considered while tuning.

Finally, in order to make your lives easier, do not modify your guitar setup too frequently. Once you have found the right strings for you, try to change them regularly using the same kind and brand: a quality new set is always the first step towards a better intonation!

Fabrizio Dadò

(*) F.Jahnel, Manual of Guitar Technology: The History and Technology of Plucked String Instruments - Bold Strummer Ltd, 1981

D.Erlewine, Guitar Player Repair Guide - Miller Freeman Books, 1990.